The Transvaal Rebellion, or first the Boer War, began on the 16th of December 1880 with the immediate spark of the uprising being ignited by an overzealous campaign to prosecute tax evasion among the Boer. It is also worth noting that the British had invested huge amounts of capital into the Transvaal (formerly the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek or ZAR) after its annexation in 1877, as it was a poorly run, bankrupt and faced an imminent Zulu invasion. Not only did the British dismember the Zulu Empire but British soldiers also defeated the Pedi tribe, which had plagued the ZAR for decades. In comparison to the Transvaal, the independent Orange Free State was a well run country with a functioning economy and civil service that was remarkably more stable than its Northern neighbour. When magistrates at Potchefstroom seized the wagon of P.L. Bezuidenhout in early November and put it up for auction one hundred armed burghers arrived under Piet Cronje to defend their countryman. In an attempt to dislodge the Boer, Colonel Owen Lanyon sent for troops and when reinforcements from the overstretched and undermanned garrison at Pretoria arrived a stand-off ensued, and war became inevitable.

On the 13th of December 1880 the Volksraad was reconstituted and a triumvirate was elected consisting of Paul Kruger, Piet Joubert and Marthinus Wessel who 3 days later proclaimed the restoration of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek. The rebellion was perfectly timed as the newly installed Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Natal, Major-General Sir George Colley was preoccupied with two far more pressing rebellion that had broken out months earlier in Basutoland and Transkei. The British garrisons of the Cape and Natal had been severely depleted and the pool of volunteers that could be recruited from the local British community had also dried up.

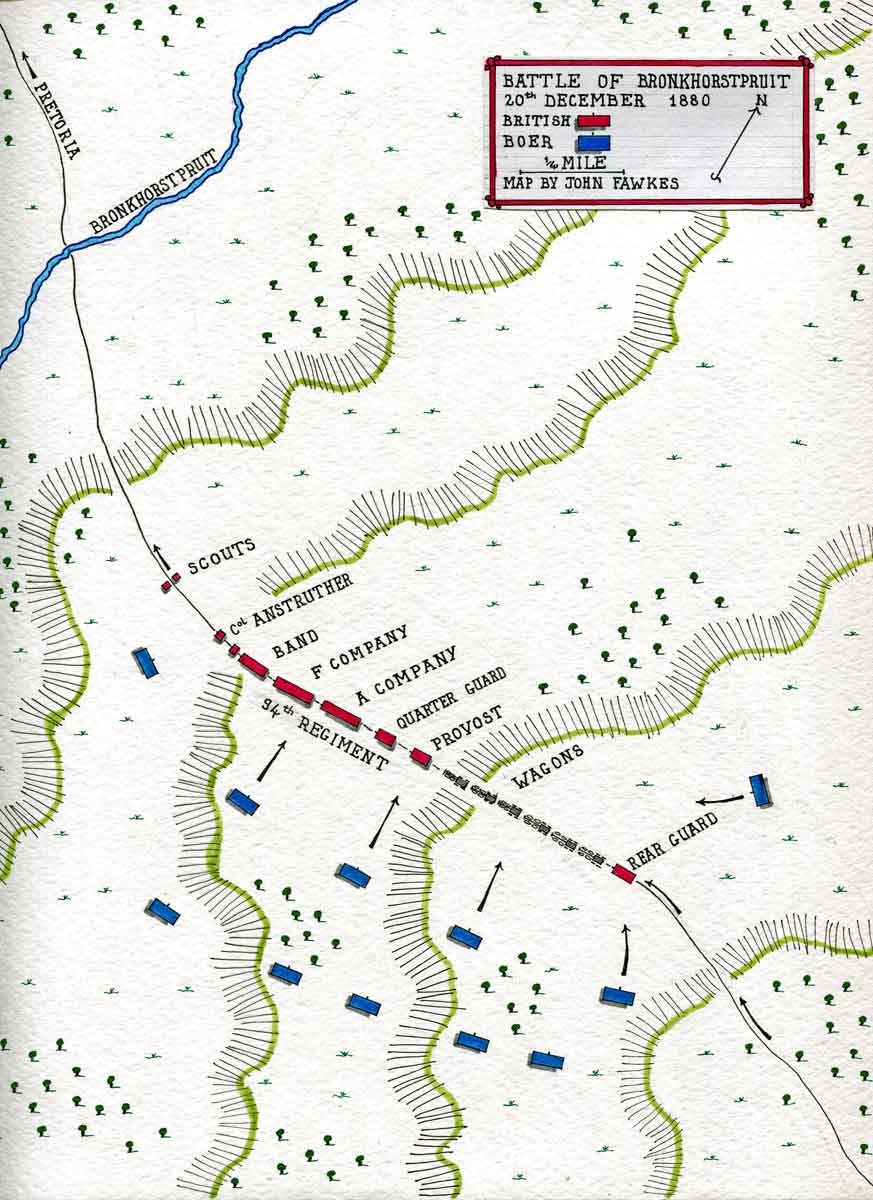

The first shots of the war were fired on the 16th of December at Potchefstroom and after ordering the insurrection be quashed Lanyon foolishly refused to concentrate his limited force of around 1,500 men in Pretoria. It was not until the 19th that news of the rebellion reached Colley, and he immediately started assembling a field force to relive the besieged garrisons. The first battle of the war took place the following day at Bronkhorstspruit when a 268 column of the 94th Regiment under Lt Col Anstruther was ambushed on the road to Pretoria. After being approached by a Boer messenger handing over a letter informing him that war had been declared and telling him to turn back. Having read the letter he refused but in the corner of his eye he saw Boer commandos advancing to within 300 yards of his column. He rode back ordering his men to take up skirmish positions and to distribute ammunition, but it was too late and hell was unleashed. 156 men lay dead or wounded, including the commander and the British grip over South Africa became ever more precarious. Due to poor communication Anstruther had no idea that hostilities had broken out having been ordered to Pretoria from Lydenburg, a distance of at least 178 miles, before the ZAR had been reborn.

Colley was desperately short of artillery and mounted men, and because of the ongoing rebellions in the Cape he would only receive reinforcements by sea which would arrive by February 1881 at the earliest. On the 24th of January 1881 the Natal Field Force (NFF) had concentrated at its forward base in the village of Newcastle on the border of the Transavaal, Colley had only manage to scrounge together a force 1,462 strong including 150 cavalry and 4 artillery pieces. He had no idea of how large the Boer force occupying Laing’s Nek was, but he had total faith in the force of the professional soldiers under his command.

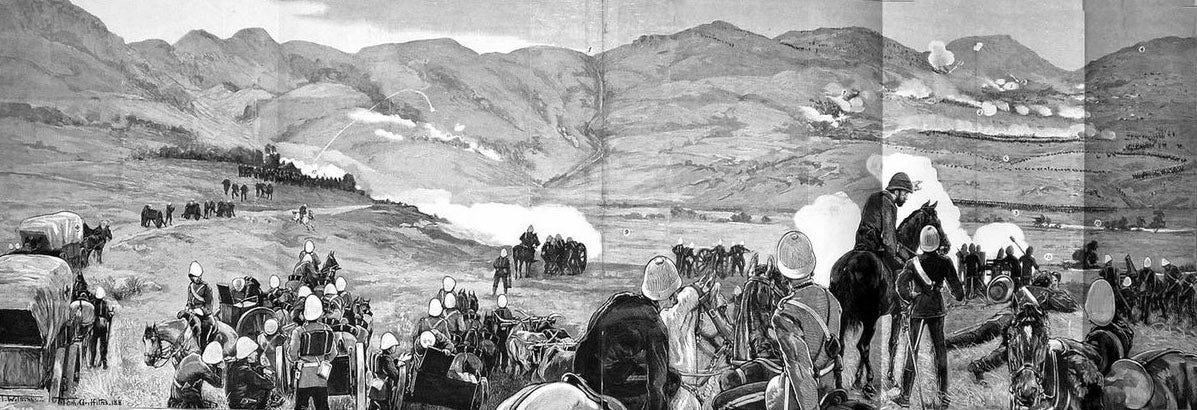

The battle began on the 28th of January with a short artillery bombardment that peppered the Boer defences but doing no real damage to the defenders, this was followed up first by a mounted charge that was quickly repulsed. The Boer forces then began to advance so as to be able to outflank any follow up charges meaning when the 58th was sent its flanks were exposed to accurate and overwhelming fire. After a series of futile bayonet charge a truce was called and the British withdrew leaving 200 casualties, including a large number of Colley’s staff. This happened as the advance of the 58th was coordinated by the Field Forces Adjutant-General and three other mounted staff officers that hurried the men up a steep slope right into the Boer line. If Colley had any inclination that were up to 3000 Boers in and around the area of Laing’s Nek he would have waited for his reinforcements. The deficiency in British numbers was also compounded by the fact that the manoeuvres to place the men in position took place in broad daylight in front of the Boer instead of under the cover of darkness. If the British had launched an attack just before daybreak the courage of the men would have had a greater effect in piercing the Boer defences

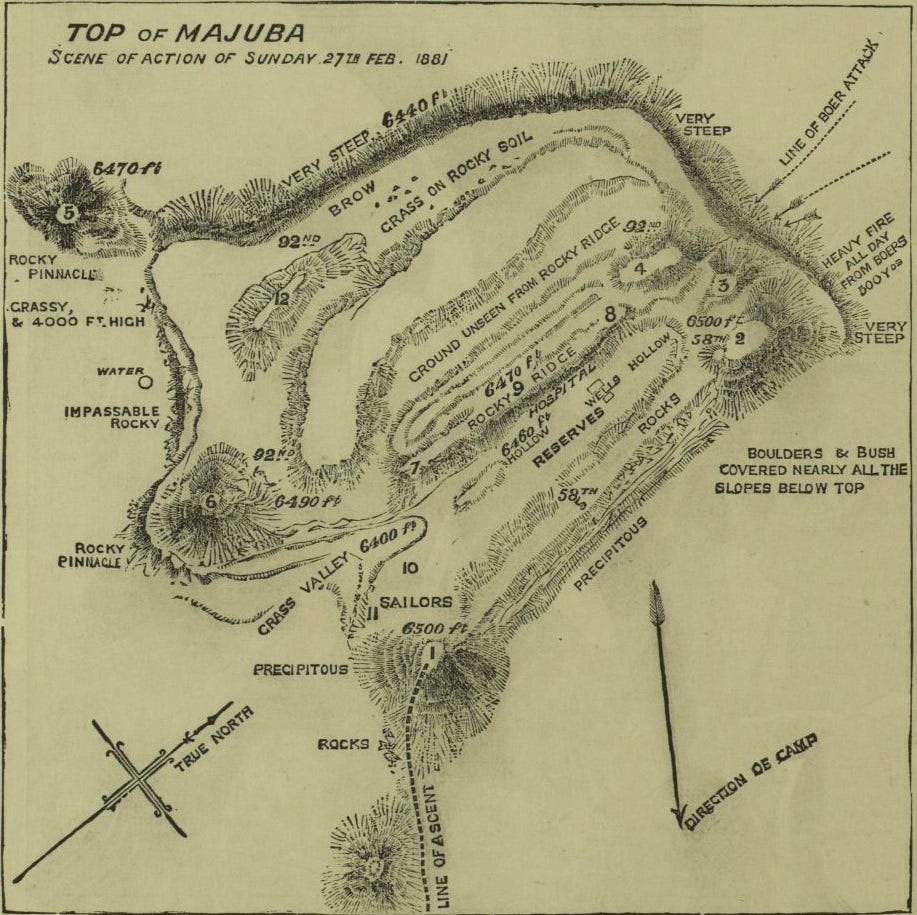

Colley decided to make a demonstration of his resolve to stay in the Transavaal and strengthen his position by removing the threat his lines of communication to Newcastle. On the 8th of February he led a force of 273 men from the 60th Rifles to a triangular plateau called the Schuinshoogte a mile and a half south of the Ingogo river. All troop movements taking place in broad daylight under close Boer surveillance. When the British reached their position they were rapidly encircled by a 250 strong commando under Nicholaas Smit who almost immediately began attacking the position. For five hours the 60th faced continuous fire from all sides and suffered heavy casualties. The ground was undefendable and Colley ordered a retreat once night fell, leaving behind half his force dead or wounded. By this point the Gladstone government was desperately seeking to end the conflict, being far more concerned with the Irish Land War, and on the 16th February the Earl of Kimberley authorised Colley to suspend hostilities and seek a peace arrangement. Colley, however, had no intention of ending the war as the forward elements of Evelyn Woods force, the 92nd Highland Regiment and Hussars, had arrived at Newcastle. After giving the Boers 48 hours to respond to his request, it would take days for any letter to reach Kruger and the triumvirate, he launched his last gamble and occupied Majuba hill on the night of the 26th of February.

The British Empire was built as a result of commanders on the ground acting independently of London and banking on a quick victory to smooth over disobeying orders and any backlash. This was how Clive took India, he took advantage of the months long travel time between Calcutta and London to do what he saw fit. We should be unsurprised that Colley did the same. He personally commanded a 568 strong force to seize the undefended hill. Once satisfied with his position he reorganised his force moving men to secure his line of communication leaving 401 men on the summit. Colley, however, neglected to order any perimeter entrenchments to be constructed, leaving junior officers to hastily construct a series of unconnected breastworks. The Boer were initially panicked as their defensive line had been outflanked, but these fears quickly faded away when it became apparent that there were would be no supporting attack on Laing’s Nek itself. This left them free to focus entirely on destroying the force that had occupied Majuba.

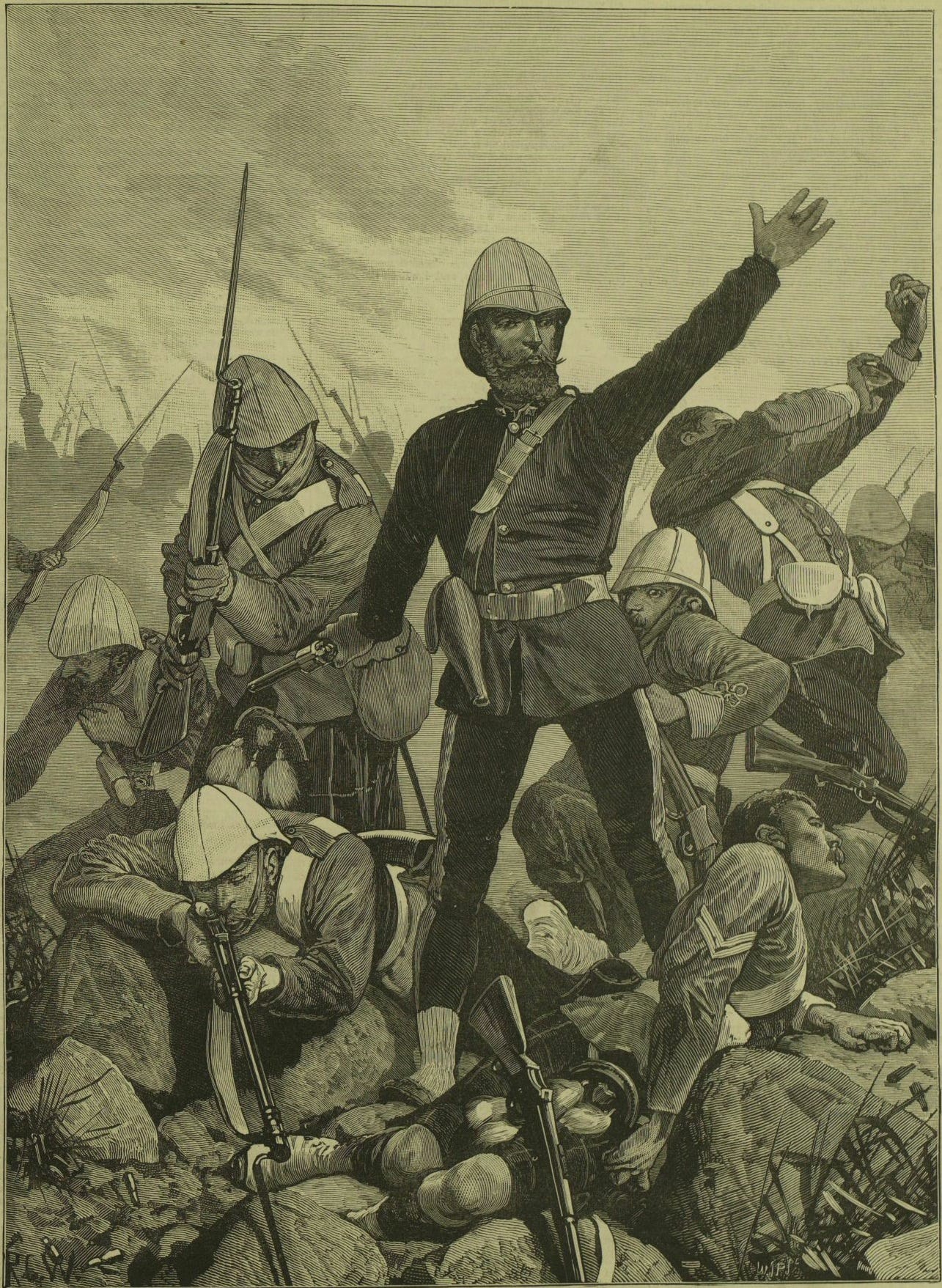

Smit sent 150 mounted men to the western side of the summit to cut off any potential retreat while 450 burghers assaulted the British in two lines with ample covering fire. By 10:30 the the British were almost completely suppressed with few soldiers willing to expose themselves to shoot down the hill. Between 12:30 and 12:45 the Boers launched their pincer attack and stormed the British defences breaching the line. This started the British retreat which began as an orderly withdrawal but within an hour devolved into a rout with men hurling themselves down the hill. This was likely sparked by the sudden death of Colley who was shot in the head during the Boer breakthrough. At 1:45 the troops guarding the lines of communication came under attack, they immediately sent for reinforcements from Mount Prospect Camp to cover the retreat bringing forward Gatling guns and 9-pounder cannons to bombard the attackers. In the camp frenzied preparations took place for fear of another Boer offensive, but the defences were judged to be too strong by Smit and the firing stopped at 3:30

With Colley dead Evelyn Wood was sworn in as acting Governor of Natal and given command of the Field Force. He was surprisingly buoyant about his prospects as soon he would have 15,000 troops in the field, almost double all the soldiers the Boer had at their disposal and enough to guarantee the success of his offensive. However, he instead was straddled with reaching a settlement with the ZAR, something he privately lambasted as an “abject surrender”.

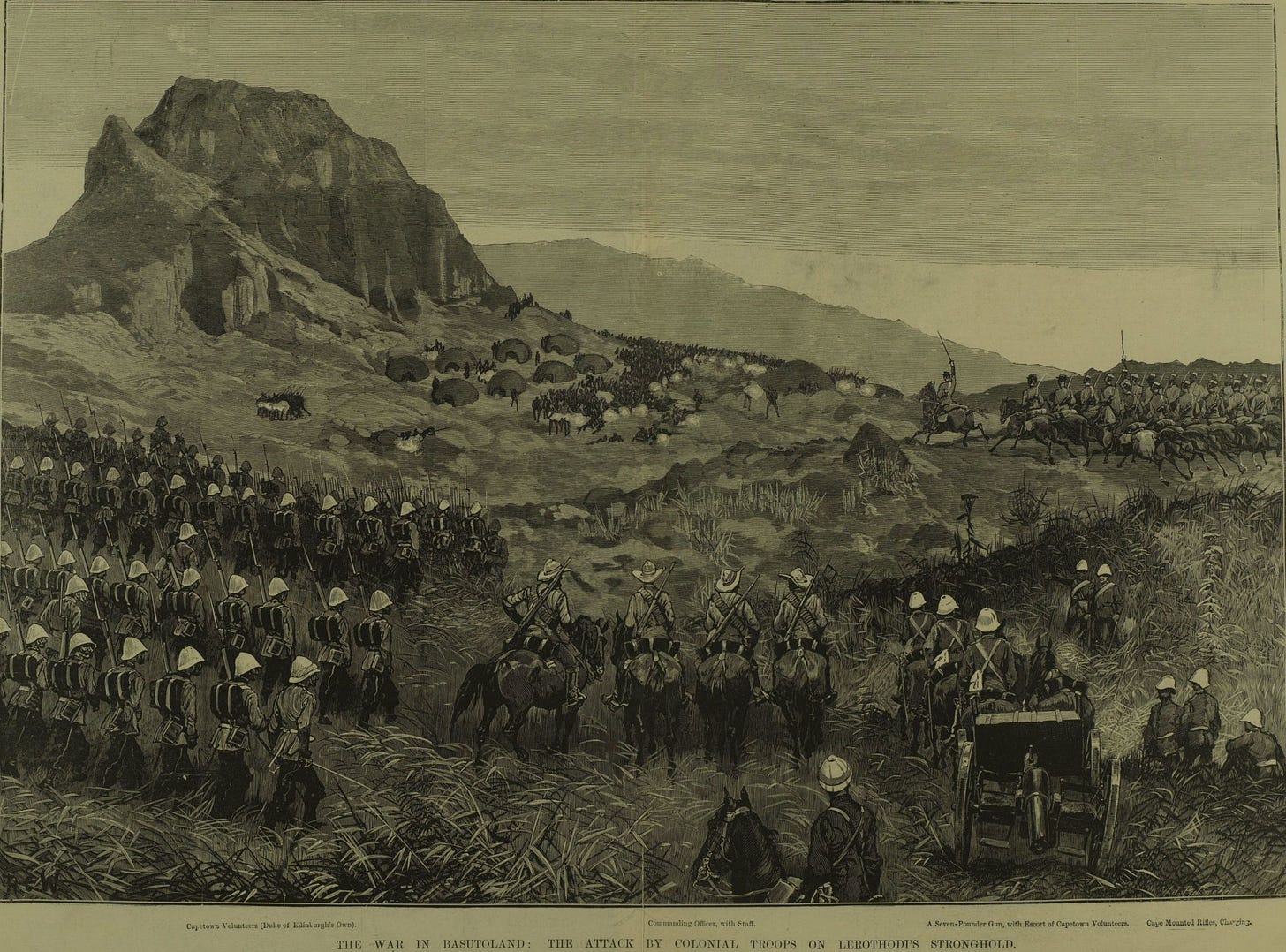

In my mind their are three main reasons as to why the British lost the First Boer War, and why they were unable to win it. The primary reason was that there were simply not enough men available to supress the rebellion, meaning soldiers would have to be brought from India and Britain. This shortage of manpower was a direct result of the Basuto and Transkei rebellion, these also served to distract the authorities from the growing anti-British sentiment in the Transvaal which delicate diplomacy could have resolved. The Basuto Rebellion had begun in September 1880 and Lieutenant-Colonel F. Carrington who had been ordered to supress it had a larger force than the initial NNF. Carrington started the war with 2000 men under his command half of which were Yeomanry and mounted troops along with five artillery pieces rising to 4000 troops in total, but he was facing 23,000 rebels.

A similar situation occured with General Charles Mansfield Clarke who was tasked with suppressing the Transkei with rose up a month later than the Basuto. He also heavily recruited volunteers from the British communities in the cape, drawing heavily on those men that had served in the Zulu war as auxiliaries who likely would have proved equally as effective as the Boer. Clarke ultimately found 900 volunteers to bolster his force, but he also had an difficult time arming them with rifles having to resort to giving some of them muskets. Ultimately the Transvaal rebellion was the rebellion that pushed the local British and colonial militaries to the breaking point. If Colley had an equivalent number of mounted troops under his command there would have been the capability to scout the Boer forces and outflank their positions. However, there is no guarantee that they would have been used effectively and might also have just been flung head first into rifle fire as well.

The second reason as to why the the British failed was that the officers and soldiers were unprepared to fight the Boer, especially as British officers completely underestimated the fighting spirit and ability of their opponents. Due to the small size of the force, staff officers were perhaps empowered to exercise complete authority over any operation. It is likely that Colley developed this habit from his mentor Garnet Wolseley, who exercised complete control over any operation he commanded. This central command discouraged junior and midranking officers from taking the initiative. Officers also made amateur mistakes such as moving troops during the day and failed to conduct coordinated attack. Soldiers were also ill-prepared as in almost all cases they needed the help of officers to sight their rifles. It can not be denied that the use of regimental colours and brightly coloured tunics made fighting much more difficult, giving the commandos far easier targets. Interestingly enough, when the Highlanders arrived from India they were in fact dressed with in Khaki, which had first been used on the North-West Frontier in the 1850s.

The final reason as to why the Boer war ended in defeat was the fact that the government had no wish to fight it. The Galdstone administration wanted to avoid costly colonial adventures after the Zulu war and were far more concerned with the growing agitation in Ireland over land reform that threatened to turn into full scale war. Additionally, Gladstone himself sympathised with the Boer aspiration for self-determination and wanted to rework the policy of confederation. Ultimately, when faced with a series of humiliating defeats and the prospect of the an even longer campaign to supress the Transvaal reasonably sought to bring the episode to a speedy conclusion and recognised the independence of the ZAR subject to British suzerain rights.

The Boer war was a total defeat for the British, but it should only be viewed as a regional one. Less than a thousand men had been killed or wounded and Britain was still the undisputed paramount power in South Africa, and with confederation abandoned anti-British sentiment in the Transvaal and Orange Free State was neutralised. The war had no impact on broader Imperial policy, much like with the First Anglo-Afghan war where the British secured complete dominion over India in 1849 7 years after the disastrous retreat from Kabul. Under the stewardship of Cecil Rhodes the Bechuanaland Expedition bloodlessly annexed the ZAR backed Boer states of Stelland and Goshen and expanded British influence across the Zambezi establishing the Rhodesias. Nor did defeat in the Boer war impact the fighting spirit of the British officer class or weaken the Governments will to use force, as in 1882 the Anglo-Egyptian war began with the country being rapidly subjugated in three months by Garnet Wolseley.